Chesapeake Almanac Podcast

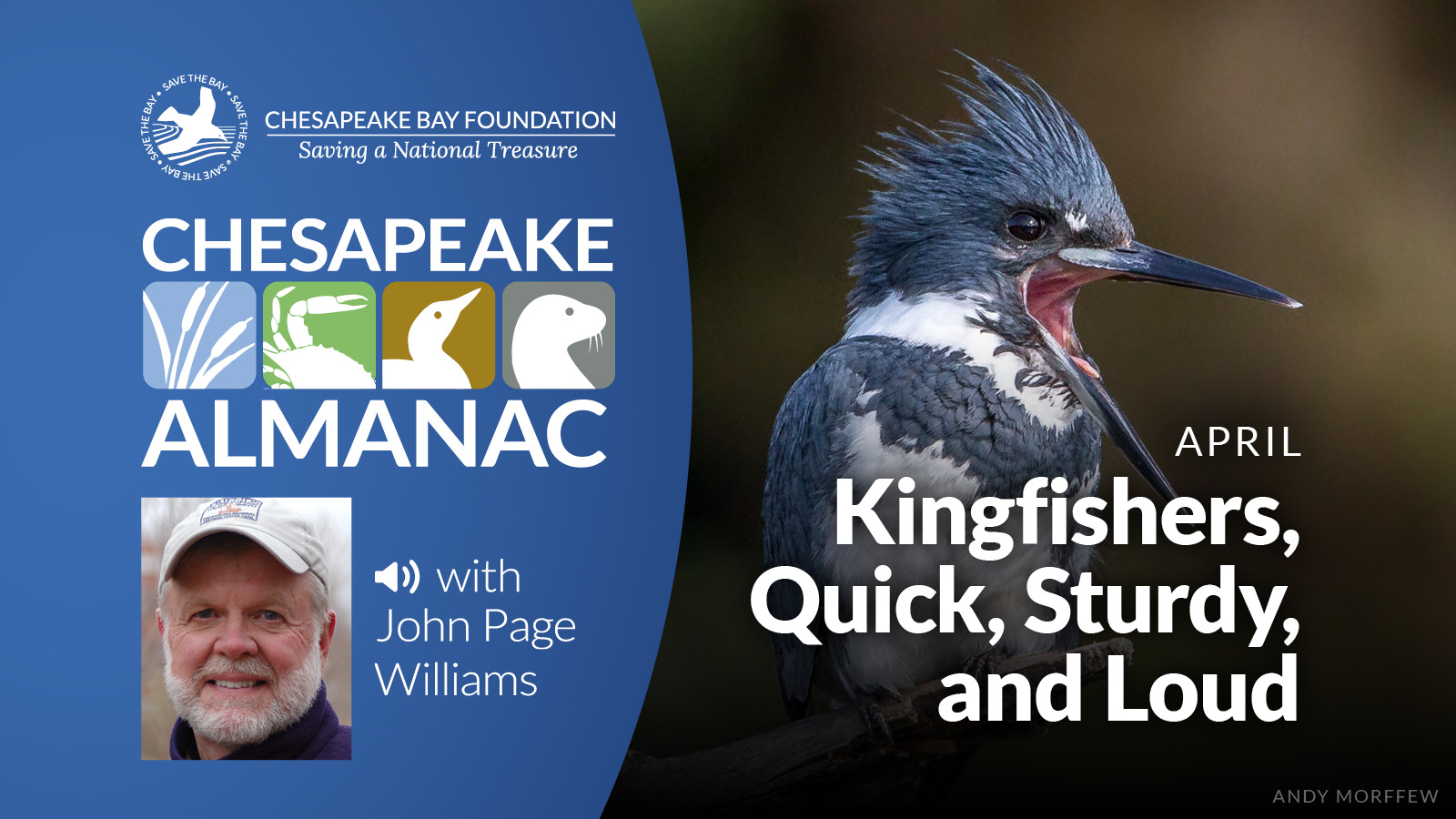

Episode 6: April: Kingfishers—Quick, Sturdy, and Loud

Copyright © John Page Williams Jr. All rights reserved.

This is John Page Williams with another reading from Chesapeake Almanac. This reading is from April and the title is "Kingfishers: Quick, Sturdy, and Loud."

"I've never been able to catch a kingfisher on film. They're too quick for me. Sorry," said Bill Portlock over the telephone. I had called him in search of a photograph for my column. Portlock is a superb field naturalist and educator recently retired from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, and also a superb photographer, who lives near Bowling Green, between the Rappahannock and Mattaponi rivers. The fact that the Bay Country's kingfishers have stymied him is strong testimony to their speed.

The well-stocked Chesapeake is home to a lot of fishing birds. Half a dozen species of gull, three or four kinds of turns, nine species of herons and egrets, plus ospreys and loons, are all successful in their niches.

Creeks and coves with high, sandy, wooded banks and shallow flats are full of tasty little fish, and the dominant fisher here is the belted kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon). The banks provide nesting habitat, the trees good perches and lookouts, and the flats plenty of food.

Virtually every long river from the James to the Susquehanna has a healthy kingfisher population, especially in upriver sections where strong currents and meander curves create high banks. Shorter, brackish rivers with wooded banks like the Severn and the Wye have their share of the birds as well. Boating people who cruise out in the open water are generally unaware of the bird, but gunkholers, inshore fishermen, and canoeists, kayakers, and stand-up paddleboarders know this aggressive blue-and-white bombshell well. It flies out to complain about their presence in loud, chattering kingfisherese.

Compared to ospreys and herons, which average 25 to 50 inches tall, the kingfisher appears small, only about 13 inches in height. The bird is nearly as large as a common turn, but much bulkier. Not only is its bill stout, but its head is large, its neck is short and thick, and its body stocky.

The kingfisher's unique build contributes to its food-catching skill. With some luck, a careful observer can witness the bird as it watches for prey from a high perch in a tree or, if necessary, hovers over the water. Once it spots its target--small fish, generally two to five inches in length, like silversides, killifish, anchovies, and menhaden--it dives precisely, grabbing the prey with its powerful bill. The kingfisher can swim underwater with its wings if necessary.

Once the prey is caught, the bird uses its broad wings to get aloft again, shaking itself in midair, just as ospreys and turns do. Then it flies back to a perch, bangs that fish's head on a limb to subdue it, and swallows it head first.

The kingfisher's heavy bill and blocky design help helpful for more than just catching fish. The male bird uses his bill to drill the nest burrow into a creek bank. With his powerful wings, he flies at the bank, chipping out dirt until the hole is large enough to create a ledge on which to perch. The big head and bull neck are well adapted for this avian battering ram operation.

Once the male can perch on the edge of the burrow, he uses his bill and feet to hollow out a burrow that's one-and-a-half to three feet in length, (sometimes longer), rising gently to a nest cavity.

Throughout their range, on rivers and creeks across the United States, kingfishers nest in risky places. Steep banks guarantee minimal interference from egg-loving predators like raccoons and black snakes, but the trade-off to that protection is the threat of flooding during storms, especially on small streams.

In April, the female lays a clutch of six to eight eggs, which the male incubates for 23 days. Then the male and the female feed the young for another 23 days until they are fledged. Laying eggs is a big effort for the female. The male shoulders most of the responsibility for parental care, giving her time to recover. Then, if the first clutch were killed by a flood, she could lay a second. Kingfishers are survivors.

The aggressive behavior we associate with kingfishers is part of the species overall survival strategy. The birds are extremely territorial, defending both good fishing flats throughout the year and good nesting banks during the breeding season. When an intruder comes into a bird's territory, it will fly to scold and complain. It will follow the intruder to the edge of its territory and then double back, because to encroach on the next bird's territory is to risk loud confrontation and another fight. Kingfishers do not attack humans, but their bank- digging and fishing capabilities can make them vicious fighters.

It's odd to find that such an active, brightly colored, loud bird as the kingfisher is so unknown to boating people. If you don't recognize these birds, look for them this year. If you do, you're already aware of how much fun they are to watch.

For more happenings around the Bay in April see our other Chesapeake Almanac podcasts and read our blog posts "Homebound Birding" and "Springtime Silver in the Rivers in April."

Subscribe to this podcast at https://chesapeake-almanac.captivate.fm/listen