The annual survey of blue crabs in the Chesapeake Bay is in, and the results aren’t good. Blue crab numbers are estimated at their second-lowest level in the survey’s 35-year history. What’s more, the results come close on the heels of the lowest level ever recorded, in 2022. Besides sending an unfortunate signal about the likely cost of summer crab feasts, the latest numbers are yet another distressing indicator that things aren’t alright for one of the Bay’s tastiest—and valuable—creatures.

What Do the Latest Survey Results Tell Us?

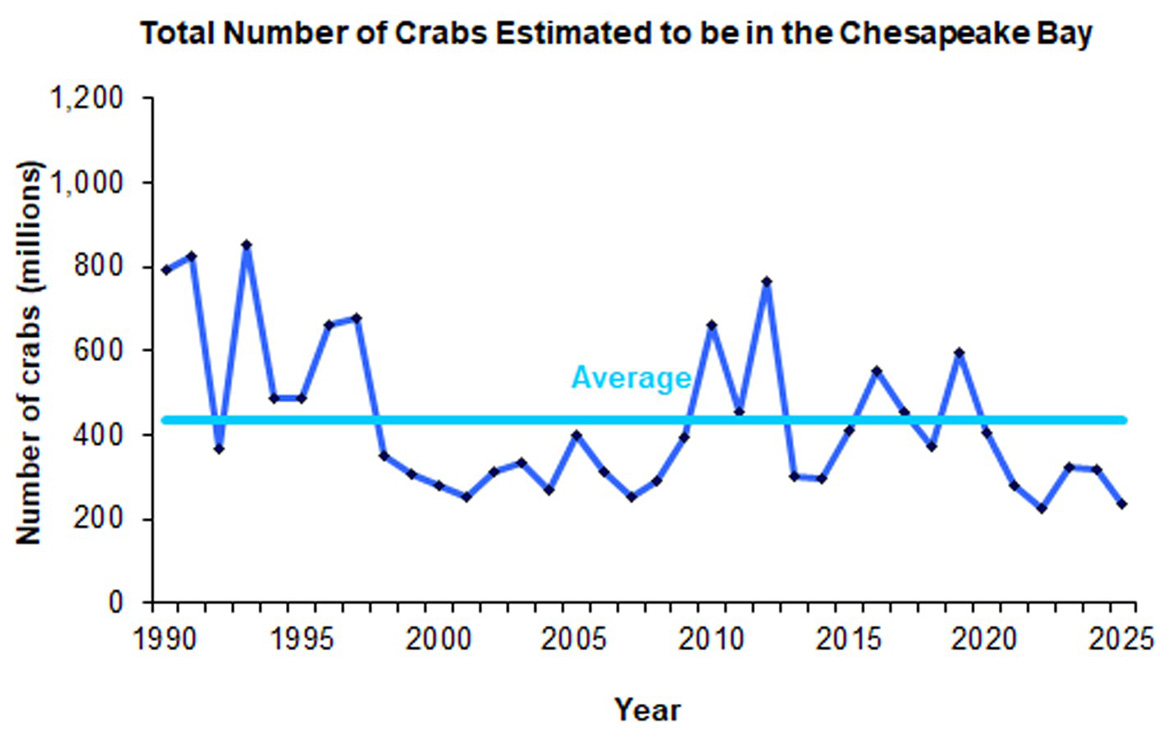

The number of blue crabs estimated to live in the Chesapeake Bay this year is 238 million. That sounds like a lot, but it’s a nearly 25 percent drop from last year and is well below the long-term average, which hovers just over 400 million crabs.

Maryland and Virginia estimate the number of blue crabs annually through the Winter Dredge Survey, which they’ve conducted since 1990. The population numbers fluctuate yearly, in part because blue crab survival depends on having the right weather and habitat conditions—and not too many predators—in a given year. With most crabs living just two years, one bad year can make a big difference and lead to major drops in the population. On the other hand, one good year can also send numbers soaring upward.

“These are a very short-lived species,” says Chris Moore, CBF’s Virginia Executive Director. “When we don’t have successful reproduction every couple of years, it’s hard to turn around the numbers of the overall population.”

MD Department of Natural Resources

What’s so concerning now is that this year’s poor results aren’t a one-off event; crab numbers have been relatively low for a while now, with the two lowest-ever numbers recorded in the past five years. In addition, this year’s results show that crab numbers are declining across all parts of the population—females, males, and young crabs. In fact, the number of young crabs has been historically low for five years in a row, even though there seem to be enough female crabs to sustain the population.

Taken together, these indicators are warning signs that there is likely something else going on beyond normal boom-and-bust cycles. That raises major concerns for the future of the species.

Why Are Blue Crabs Declining in the Chesapeake Bay?

The reasons behind the recent declines are still unknown. Cold weather may have been a factor this past winter, but scientists have multiple theories about what might be keeping crab numbers lower over the last several years, including:

Changing conditions in the ocean

Blue crabs spend approximately the first month of their life in the ocean as larvae. They depend on favorable winds and ocean currents to carry them back into the Bay’s rich, shallow-water nursery areas, where they find food and shelter as they grow. Shifts in these weather patterns due to climate change could be affecting how many crabs make this journey successfully.

Changing habitat

A blue crab sloughs its shell in a protective bed of Bay grasses. Blue crab habitat, important for both food and protection from predators, can fluctuate with water quality and temperature.

Lori Rossbach

Once they are in the Bay, young crabs are primarily looking for places to hide from predators and find food. Underwater grasses are an important habitat that provides both. But the Bay’s grasses have been depleted by pollution, and one once-abundant species—eelgrass—is vulnerable to rising water temperatures and heat waves caused by climate change. Salt marshes, another important habitat, are also at risk as shoreline development replaces natural marsh with hardened barriers. A study by researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) found that for every 10 percent increase in shoreline hardening, crabs in the area decrease by four percent.

More predators

A fisheries biologist with the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries examines a blue catfish caught during a research monitoring program in the James River.

Matt Rath/Chesapeake Bay Program

An increase in the fish that eat blue crabs, particularly invasive blue catfish, could also be making it harder for young crabs to survive. For example, another study by VIMS in 2021 estimated that invasive blue catfish in just a small section of the lower James River ate approximately 2.3 million blue crabs annually. Red drum, another fish that preys on blue crabs, are also moving into the Bay in greater numbers, likely due to warming waters.

Pollution

In addition to negative effects on habitats like underwater grasses, pollution creates areas of water in the Bay with low—or sometimes no—oxygen. These ‘dead zones’ most often occur in deep water, which crabs use to migrate. While crabs can avoid the dead zones, doing so could be concentrating them in areas where they are more vulnerable to predators, including humans. These areas can also become devoid of food that blue crabs would otherwise be feasting on.

What Can We Do to Help Blue Crabs in the Chesapeake Bay?

This population doesn’t recognize or respect jurisdictional boundaries, so it’s very important that Virginia and Maryland work cooperatively to manage the species.

Maryland, Virginia, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are investigating many of these pressures and their connection to the blue crab population as part of an updated Bay-wide stock assessment, due out in 2026. The assessment should help fishery managers identify the most critical problems and recommend changes to management to mitigate their impacts.

In the meantime, it is important for the states to manage their blue crab fisheries collaboratively and with caution. CBF is calling for both Maryland and Virginia to consider further protections for the species.

“Blue crabs are extremely unique in their life history. They travel throughout all portions of the Bay,” says Allison Colden, CBF’s Maryland Executive Director. “This population doesn’t recognize or respect jurisdictional boundaries, so it’s very important that Virginia and Maryland work cooperatively to manage the species.”

In Maryland, that means strengthening protections for female crabs and reducing the importation of egg-bearing “sponge” crabs from Virginia, as well as maintaining regulations for male crabs that were put in place for the first time in 2023.

In Virginia, CBF is urging the state to reduce the blue crab harvest and consider additional protections for males, which have reached an historic low.

“The ecosystem is showing stress, the crab population is showing stress, and so we’re going to need actions Bay-wide,” says Moore.

We are also calling on the federal government to fully fund programs and agencies—including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—that support regional clean water initiatives that protect blue crab habitat.

Rise up with us now.

Contact your members of Congress and urge them to do the right thing:

Protect environmental funding! Protect agency staffing!

Take Action