We are currently working on revamping our report. In the meantime, for more recent scientific analysis, please see the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s 2025 Bay watershed report card.

•About the State of the Bay Report

State of the Bay Report

Bill Portlock

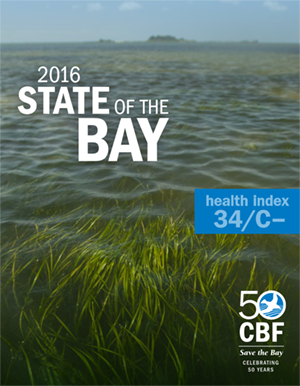

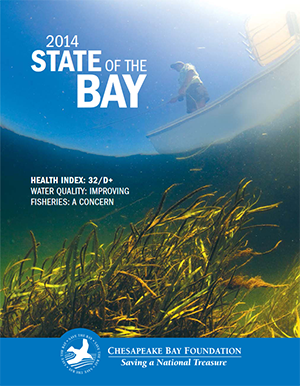

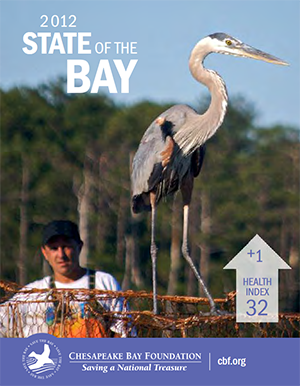

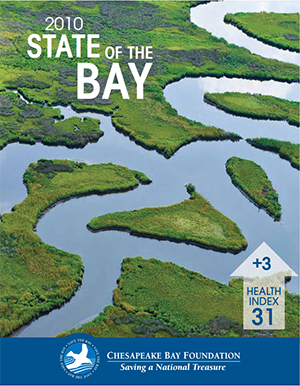

From 1998-2022, CBF's State of the Bay report tracked the health of the Chesapeake Bay and provided insight into the progress—or lack thereof—being made.