The last update to Virginia’s Clean Water Blueprint—the single most important roadmap to restoring Virginia’s waterways—is being finalized between now and June 7. Technically known as Virginia’s Phase III Watershed Implementation Plan, it has been years in the making with input from communities and stakeholders across the Bay watershed.

We are very pleased by the thoughtful and comprehensive draft released by Virginia’s Governor in early April. It clearly details the concrete actions that, taken together, will reach the Commonwealth’s pollution reduction goals by a 2025 deadline. But this draft could still be changed, and we must make sure it isn’t weakened in the coming weeks. We need your help to get it over the finish line.

Five key proposals we hope to see in Virginia’s final Blueprint:

- Climate Change: In this draft, Virginia is a regional leader in accounting for pollution increases due to climate change, which is already harming the Bay. To be prepared for the future we must start working now to address this growing threat to our waters.

- Agriculture: Virginia’s farmers have made significant headway in reducing pollution to the Bay, but work needs to be accelerated. Virginia’s draft would do more for fencing livestock out of streams than any previous Virginia plan. It calls for more funding, more flexibility, and for the first time a deadline for fencing livestock from 100% of perennial streams. It also relies on other important farm conservation practices, including requiring plans to scientifically manage nutrient pollution on 85% of cropland.

- Sewage Plants: Upgrades for sewage treatment plants have already significantly reduced pollution discharges. This has made a big difference so far, but sewage plants can do more to help restore rivers and the Bay. That’s exactly why Virginia is proposing more pollution reductions from some facilities.

- Development: Virginia’s update to the Blueprint takes aim at reducing polluted runoff from developed areas, a major challenge to cutting pollution. That includes considering updated rules for controlling construction-related stormwater and increased state support for the Stormwater Local Assistance Fund. Virginia will also look into expanding protections from the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act—which currently only protects waterways and sensitive areas from development in eastern Virginia—to areas west of Interstate 95.

- Lawn Fertilizer: Virginia is calling for more action to reduce pollution from the fertilizer applied to lawns and other turfgrass in urban and suburban areas. There are a million acres of turfgrass in Virginia’s Bay watershed. Properly managing lawn fertilizer will make a big difference.

We hope to see these proposals, along with many others, in Virginia’s final Blueprint. Virginia has made substantial progress so far. Nitrogen pollution is decreasing, oxygen-starved dead zones in the Bay are shrinking, and underwater grasses are growing at record levels. But the Bay’s health is still just a fraction of what it once was. The recovery is fragile, as shown by the record rainfall and increased polluted runoff of 2018. Without accelerated efforts, promising gains could easily be reversed.

Work under the Blueprint beautifies communities, grows local economies, and improves quality of life. Once fully implemented, the Blueprint will provide $8.3 billion in economic benefits from nature annually for Virginia. Below is a sample of what we’ll see more of if Virginia’s final update to the Blueprint stays strong. Take action now to support key proposals for Virginia’s Clean Water Blueprint.

What Virginia’s Blueprint Looks like in Your Community

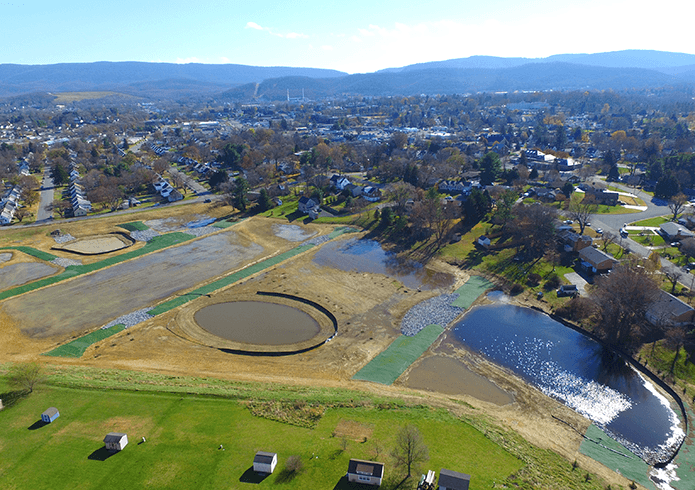

A new 10-acre man-made wetland in Waynesboro is creating wildlife habitat, anchors a neighborhood park, and reduces pollution to a stocked trout stream that brings in fishermen.

Timmons Group

A new 10-acre manmade wetland in Waynesboro is creating wildlife habitat, anchors a neighborhood park, and reduces pollution to a stocked trout stream that brings in fishermen.

A stream restoration in Fairfax County helps slow and filter polluted runoff, prevents erosion, and brightens up a park.

Fairfax County Government

A stream restoration in Fairfax County helps slow and filter polluted runoff, prevents erosion, and brightens up a park.

In Virginia Beach, cleaner water on the Lynnhaven River is supporting local businesses and a growing oyster aquaculture industry.

Kenny Fletcher

In Virginia Beach, cleaner water on the Lynnhaven River is supporting local businesses and a growing oyster aquaculture industry.

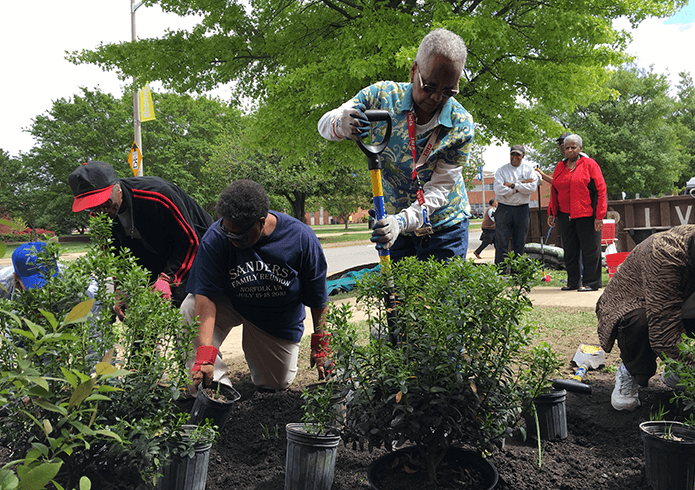

In Hampton, members of First Baptist Church planted a rain garden to reduce polluted runoff and beautify the church.

Karen Jacklich

In Hampton, members of First Baptist Church planted a rain garden to reduce polluted runoff and beautify the church.

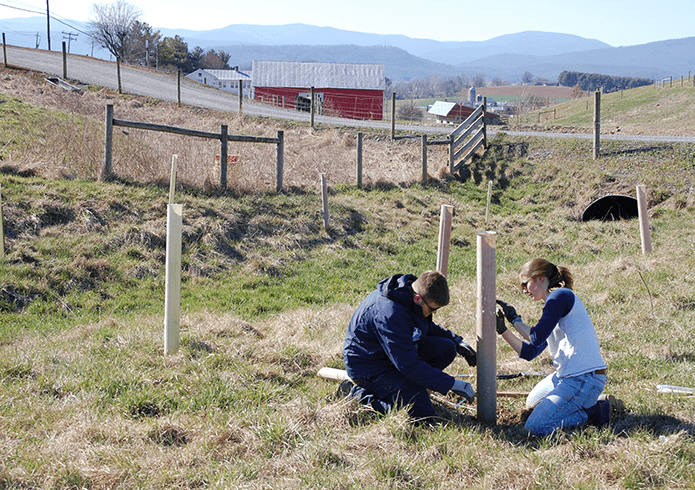

On a farm in the Shenandoah Valley, planting a buffer of native trees along a stream will reduce agricultural runoff and lead to both healthier cattle and waterways.

Kenny Fletcher

On a farm in the Shenandoah Valley, planting a buffer of native trees along a stream will reduce agricultural runoff and lead to both healthier cattle and waterways.

Ribbon cutting ceremony at the new wastewater facility at Moores Creek in Charlottesville, VA.

Doug DeGood.

In Charlottesville, a new wastewater facility has led to a cleaner Rivanna River.

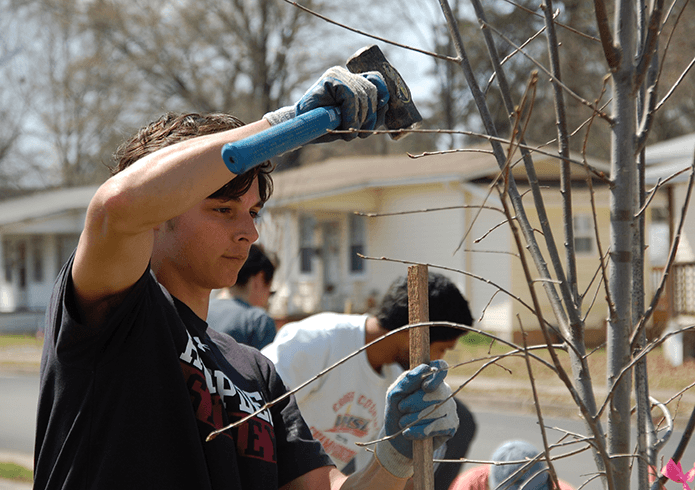

In the City of Hopewell, planting urban trees provides shade, beautifies the neighborhood, and stops polluted runoff from reaching the James River.

Kenny Fletcher

In the City of Hopewell, planting urban trees provides shade, beautifies the neighborhood, and stops polluted runoff from reaching the James River.