This op-ed originally ran in the Bay Journal.

You may not realize it, but the water we drink, shower and bathe with, as well as recreate in, was once stormwater.

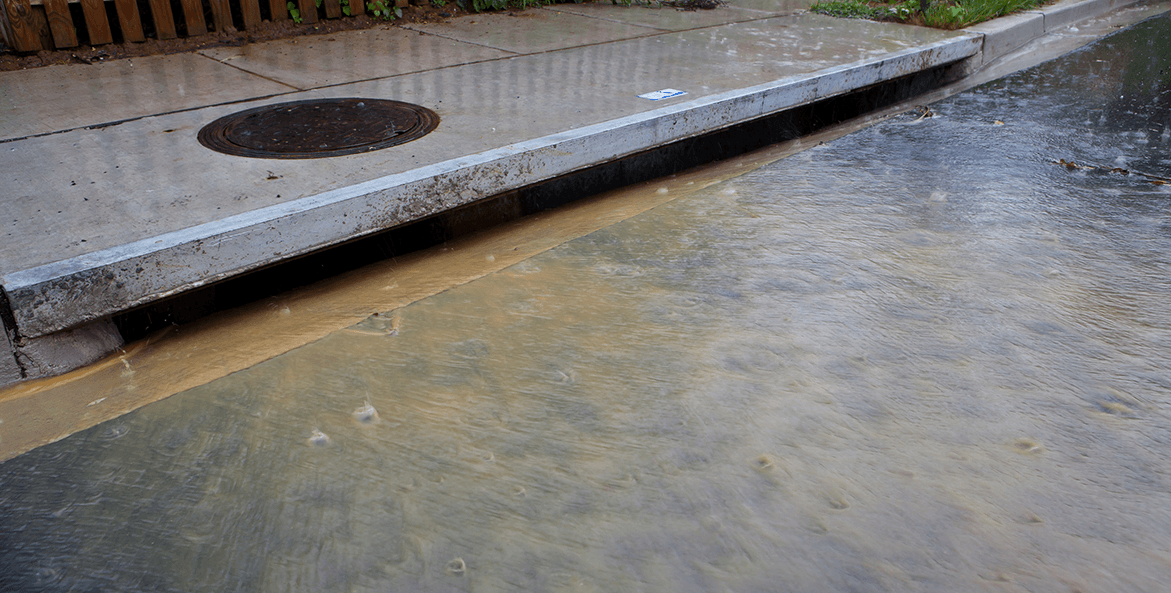

When it rains, water that runs off hard surfaces like rooftops, parking lots, roads and even lawns is often shuttled to the nearest river or stream by underground pipes and open swales. Along the way, things like motor oil, pet waste, lawn chemicals and fertilizers, cigarette butts and garbage hitch a ride.

Too much stormwater can overwhelm Pennsylvania’s undersized and undermaintained infrastructure. In many areas, this is often combined with human waste and can cause raw sewage overflows into streams and streets. Flooding plagues most of our older towns and boroughs, and floodwater is sometimes unsafe for human contact. Pennsylvania has more of these “combined sewer overflows” than any other state.

About 5,200 miles of our streams are classified as impaired from polluted stormwater runoff.

While we all want less of the dirty stuff flooding and polluting the water we rely on, agreement on how to reduce, clean and manage polluted runoff isn’t as easy to come by.

More than 1,700 governments nationwide, including more than two dozen in Pennsylvania, have chosen to establish local stormwater fees. One common feature of all of these is that they’re based on local solutions to a big problem.

As the flood of reporting about stormwater fees continues, several points deserve clarification. Back in 1987, Congress recognized that stormwater was a big and growing problem in the nation. Starting in 1990, as part of the federal Clean Water Act, municipalities of a certain size or larger were required to start reducing stormwater runoff. Today, there are more than 1,000 such municipalities in Pennsylvania.

Municipalities are not mandated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or state Department of Environmental Protection to have stormwater fees. Instead, municipalities choose how to pay for stormwater projects.

The stormwater fee is not a tax on the amount of rain that falls from the sky and onto the land. Because it is not a tax, the fee often provides that tax-exempt properties pay their fair share. Some municipalities apply calculated stormwater fees to agriculture, churches, schools and government properties. Others ask for a flat fee.

For other landowners, such as businesses, the fee is based on the property’s amount of hard surface and how much polluted runoff the property sends into the stormwater system. It’s an impact fee.

Most programs offer credits or discounts for property owners who add trees, rain gardens and other practices that reduce stormwater pollution.

Fees can vary. For example, households in the city of Lancaster, PA, pay about $0.10 a day. Derry Township in Dauphin County has a fee of $0.21 a day. The Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority fee is around $0.16 a day. People who buy fast-food coffee three times a week would pay more each month.

The revenues from fees are usually dedicated to the local stormwater authority, to be used only for reducing the amount of polluted runoff and its impacts.

One inch of rain on just one acre of hardened surface produces about 27,000 gallons of polluted runoff. That’s almost enough to fill a large, in-ground swimming pool. For most local systems — some of which haven’t been maintained or updated for 25, 50, even 100 years — the water hits our streams hard and fast. It blows them out of their banks causing flooding to roads, downtowns, backyards and basements.

A recent opinion piece that appeared in a number of Pennsylvania newspapers called for the state DEP to provide “substantiated, comprehensive data” of local water quality and plans for monitoring improvements.

There’s a surprisingly large amount of stream water quality monitoring data in Pennsylvania already. It’s been collected by federal and state agencies, academic institutions, and even local watershed groups sometimes for decades. Much of it, after review for accuracy, is used to help scientists understand what’s going on in our streams and why.

Models, however, do something monitoring simply can’t. They’re used to predict the outcomes of different scenarios, sometimes including cost estimates that can ultimately save citizens money.

More monitoring can be helpful. But without increased investments in the programs and people to make it happen, the question becomes how will the monitoring be done and by whom? DEP staffing is at levels comparable to those in the mid-90s, and the water programs have been chronically underfunded for more than a decade. The governor’s 2020–21 budget proposed that DEP funding rise above 1994–95 levels for the first time in a decade.

Another point worth clarifying: The Chesapeake Bay Foundation has not said it will sue Pennsylvania for being significantly behind in meeting its clean water commitments. The state of Maryland has said that. Both Maryland and CBF have said that the EPA is subject to suit for not holding the commonwealth accountable for repeatedly missing its targets.

Locally created and controlled stormwater programs are critical to ensuring that we have clean and abundant water.

Our health, well-being and quality of life depend on it.

Issues in this Post

Runoff Pollution Land Use Runoff Pollution Stormwater Runoff in Pennsylvania Water Quality