This is the second in a series of stories about the great clean water work that is happening upriver in West Virginia, Delaware, and other states that don’t directly border the Bay. Much of the funding and resources for this critical work are only made possible through the landmark 40-year Bay partnership, a collaborative effort between states, the federal government, and local partners to reduce pollution and restore habitats across our remarkable watershed.

Bringing brook trout back to their native waters in eastern West Virginia isn’t just a job for Brandon Keplinger. It’s a mission.

Like many West Virginians, Keplinger feels a personal connection to the only trout species native to his home state. As a district fisheries biologist with the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources, he is dedicated to rebuilding brook trout populations in the Eastern Panhandle where they once thrived.

The better stewards we are up here, it certainly improves conditions in the Bay.

Keplinger and his crew are hatching eggs of “heritage lineage” brook trout collected from brook trout native to the Potomac River headwaters. Partnering with Trout Unlimited and its Potomac Headwaters Home Rivers Initiative, they release the juvenile fish into streams with the right temperature, pH, and spawning conditions to support this sensitive cold-water species.

Why Successfully Reintroducing Brook Trout is Important to Our Waterways

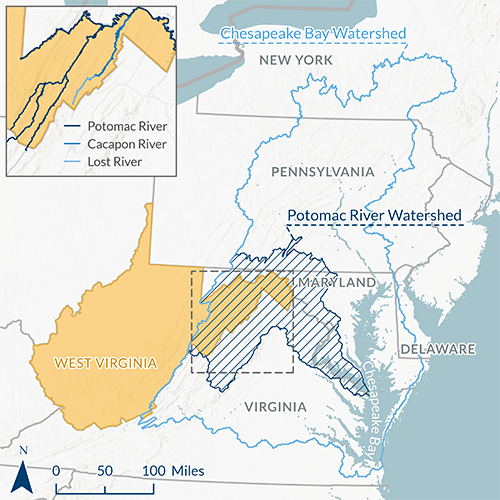

Improving water quality where the Potomac begins also helps boost water quality downstream all the way to where it empties into the Chesapeake Bay. The Potomac is the second-largest tributary of the Bay and an important source of fresh water.

West Virginia's Potomac River Watershed, part of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, includes the Potomac, Cacapon, and Lost Rivers.

Chesapeake Bay Foundation

“Everybody lives upstream. So, what flows from our state ultimately ends up in the Bay and throughout the course of the Potomac River. The better stewards we are up here, it certainly improves conditions in the Bay,” Keplinger said.

“But from a standpoint of where we are locally, it’s awesome to be able to try to restore a really, really appreciated sport fish and native fish to a region where [they are completely gone],” Keplinger added.

Brook trout need cold, clean water to survive. That makes them an important indicator of stream health. Restoring naturally reproducing brook trout populations and expanding their habitat is one of the goals of the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement signed by West Virginia, the five other states in the watershed, and the District of Columbia.

Brook trout are also vital to the region’s outdoor recreation economy, particularly in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York. While the colorful fish is popular wherever anglers cast a line for it, it is an icon in the Mountain State.

How to Create a Self-Sustaining Brook Trout Population

Keplinger hopes successfully reintroducing self-sustaining brook trout populations will inspire more West Virginians to be better stewards of the state’s invaluable natural resources—especially older folks who grew up catching brook trout in streams where they can no longer be found.

“They wish [the brook trout] were there and it was more like things were when they were younger and the way they thought the better years of their life were,” Keplinger said.

Brook trout have existed in eastern West Virginia for at least ten thousand years, he noted. “They’re more native than we are. It’s a really cool, heritage-related organism to this area, especially in the mountainous areas where a lot of my family has grown.”

Working in a Wardensville, WV, hatchery leased from West Virginia University, Brandon and his technicians only use eggs hatched from brook trout taken from the Cacapon River watershed to reintroduce into Cacapon watershed streams. The Cacapon River is a tributary of the Potomac.

Reintroducing fish from the same genetic line gives the hatchery-raised fish a better chance of reproducing successfully than if they had come from the eggs of trout outside the region, according to Keplinger.

Trout Unlimited identifies streams where the conditions are right for reintroduction and works with nearby landowners when private land is involved, said Project Manager Ryan Cooper. The group then designs and creates a natural habitat, including overhead tree cover to cool the stream, using native rock, wood, and other materials from the area.

“The idea is to create a reproducing population and then it takes care of itself and doesn’t need any man-made help,” Cooper said.

What it Takes to Fund Brook Trout Re-introduction

A mix of private and federal money funds Trout Unlimited’s work. The EPA’s Chesapeake Bay Program provides matching grants because the project improves water quality and wildlife habitat in the Bay watershed. The Bay Program coordinates the state-federal partnership to restore the Chesapeake and major tributaries like the Potomac River.

Farm Bill conservation programs share costs and offer technical assistance to the landowners letting TU do stream restoration work on their property. That’s because the trees being planted to shade the trout also help farmers keep excess fertilizer and sediment out of the stream.

The Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program, run by the Fish and Wildlife Services, also picks up some of the tab for private landowners because TU’s restoration work on their land helps increase brook trout numbers in their native habitat.

Making a Difference for West Virginians and Waterways

Regardless of where the money is coming from, the project is a hit with West Virginians. The Division of Natural Resources is getting extremely positive feedback from the public on its social media channels and from its radio outreach, Keplinger said.

Hatchery technician Rebecca Sager has seen it for herself.

“You have hard-core West Virginians that still love to fish for their native trout, and they love seeing that we’re doing things to try and help the watersheds and help keep the trout population,” she said.

When caring about their native trout means caring for their habitat in the Potomac headwaters, West Virginians are doing their part to care for the rest of the Potomac River and the Chesapeake Bay, too.

Washington, D.C. Communications & Media Relations Manager, CBF

lcaruso@cbf.org

202-793-4485